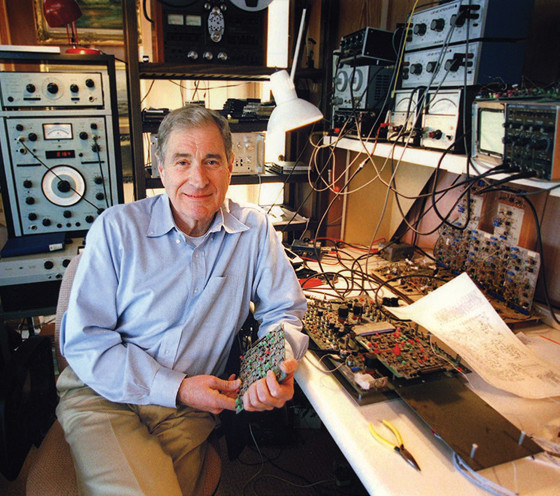

In audio, many technological advances have resulted from the work of engineers who have successfully licensed their inventions rather than bringing the products to market themselves. Successful licensors include Ray Dolby’s noise reduction and surround sound (see Photo 1), Arnold Klayman’s sound retrieval system (SRS), Oskar Heil’s Air Motion Transformer (licensed to ESS), NXT’s DML and BMR speakers and Sausalito Audio’s acoustic lens, which was developed by Manny LaCarrubba (see Photo 2) and is now the hallmark of B&O’s products. Sumitomo and Magnequech even licensed the magnetic materials used to formulate and process neodymium for speakers to Chinese vendors.

This article on business development and strategy examines licensing negotiation tactics from the intellectual property (IP) owner’s perspective. We will assume that the IP has been determined to be a valuable asset, the owner owns the IP and controls the usage rights, the IP has been cleared of any infringement liabilities, and the IP has been properly protected (e.g., copyright, trademark, or patent).

The licensing process is a major undertaking, which should not be taken at face value. Everything including the fee structure, exclusivity agreements, terms, durations, and ownership of the licensee’s further development of the base invention need to be fully considered by the licensor.

For example, the licensor may even request a “signing fee” (separate from the advance) to cover the upfront legal and other fees. There are endless issues to consider regarding licensing agreements. This article focuses on creating leverage at the negotiating table by hiring a licensing professional, designing a strategy and walk-away plan, performing due diligence, and identifying optional alternatives.

The first question every licensor should ask is: “Am I the right person to engage in defining a licensing program for my innovation or should I hire a professional to maximize the returns?” Many times the licensor believes he or she has the skill set and the negotiating proficiency to embark on a licensing program. This is the first mistake in creating leverage and being able to maximize the returns.

The engineer who wishes to license the new intellectual property rights (IPR) will most likely be dealing with experienced licensees. This is especially true with large offshore OEM/ODM factories that understand the process and will squeeze the licensor for every little drop of margin. It is important for the licensor to be part of the process, but it is probably not the best idea to take the lead in the creation of the licensing program. Creating leverage is the key to coming away with a deal that the licensor can live with for years to come. A licensing professional adds value by creating leverage even before the first negotiations take place.

Licensing professionals and subject/industry matter experts are shrewd negotiators. They also have an invaluable network of industry contacts, especially among the potential licensees. It is also important to hire an attorney who knows licensing, but his role is different from a subject matter expert who will be your licensing champion. These seasoned experts normally command a retainer plus 20% to 40% of the licensing fees. However, their skills to maneuver and create leverage for their clients outweigh their cost assuming the invention is commercially viable. There are many stories of licensors with innovative and/or disruptive IP who are only able to negotiate a fraction of the IPR’s true value.

To make matters worse, when the desperation becomes overwhelming, the licensor eventually agrees to an inferior deal. A veteran licensing agent or industry expert plays an indispensable role throughout the licensing process by structuring the overall strategy, creating the walk-away plan, performing due diligence, and identifying options.

Strategies often form along the following scenarios:

• A flat one-time fee, where the first licensee gets it below “market value” while the licensor uses the exposure for marketing purposes and to build the IPR brand. This may require the licensee to display the technology logo on the product

• Exclusivity to a launch customer brand for a time period or in a specific geographical area

• A direct deal with a premium product licensee to associate the IPR with a high-end high-quality brand

• Multiple non-exclusive licensees to either high-tonnage or high-end product lines where the IPR substantially differentiates the licensee’s product from their rivals

• Multiple nonexclusive licenses for a nominal fee, where the exit strategy is to take the company public or to be acquired

It is important that before delving into any of these scenarios the licensor knows when to walk away. Since the goal of the licensor is to maximize the agreement’s value, he/she must prepare a walk-away scenario, which enhances the leverage during the negotiation.

Knowing when to walk away and developing your best alternative to a negotiated agreement (BATNA) are crucial components in all negotiation strategies, especially when facing a powerful negotiator. If you go into a meeting desperate to close the deal, the other side will read those signals in your body language. In Roger Fisher and William Ury’s iconic bestseller, Getting to Yes (Penguin, 198) the authors explain, “The more easily and happily you can walk away from a negotiation, the greater your capacity to affect its outcome.” The authors add, “Developing your Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement (BATNA) not only enables you to determine what is a minimally acceptable agreement, it will probably raise that minimum.”

A successful negotiator creates leverage by always having a walk-away value, a well-defined BATNA, and is constantly searching for potential licensees. Novice negotiators tend to affiliate a walk-away strategy only with a bottom line (e.g., royalty payments, guarantees, advances, etc.) However, in complex negotiations with multiple variables, the licensor must create a holistic strategy in relationship-to-accounting considerations, exclusivity, indemnity, and so forth. It is essential for the licensor to keep to the script, hold firm, and know when to walk away, which are all functions of strategy and due diligence.

Performing due diligence, market research and exploration of the target licensee is yet another way to create leverage. Often the difference between a bad deal and an acceptable deal comes down to the power of due diligence. Licensors need to absorb information and identify with the licensee on multiple levels including company reputation, financial health, licensing experience, and comparable products. It is also essential that the licensor fully comprehends the IPR’s value to the potential licensee’s business model, distribution strategy, and future cash flows.

Understanding the target licensee’s financial health and the technology’s revenue forecasts is important. Protecting the IPR from going to a firm that is not financially health is also important as provisions are normally added to the final agreement that protects the licensor. Confirm your goals and objectives and fully understand the motivations of the executives, the decision-making process, and the licensee’s organization.

Once due diligence has been completed, the licensor will have a sufficient knowledge base to improve leverage by removing as much asymmetric information as possible (where one party has superior information over the other) and by identifying alternative options.

Identifying alternative options is another important way to create leverage. The astute licensor understands that the identification of alternative options is a continuous activity throughout the licensing process, rather than a one-time act during the initial strategy building session. Although it may seem intuitive, verifiable proof with a solid foundation is always comforting. Game theory is the study of strategic interactions between self-interested economic agents where outcomes are produced based on their own set of preferences.

Using the game theory approach, trained negotiators are able to study and to understand the relationship of these games to real-life scenarios. The “ultimatum game” is the closest example that mimics the results of real-life licensing negotiations. These experiments have proven that with multiple options on the table the licensor is not only more likely to accept offers, but is also more likely to receive a larger pay-out.

Once the identifiable alternative options have been established throughout the process the licensor is not constrained nor is intimidated into accepting the first and only offer. The licensor has effectively created leverage in the negotiation by having at least two offers to consider, which improves the prospect of sealing a deal closer to the “wanted” position.

A licensor who creates competition between two or more potential licensees intrinsically enhances leverage during the negotiation process. A real-life example of a licensor who developed a super high-end outdoor audio product line with huge top-line growth potential and bottom line margins only to license it for a mere fraction of the real value exemplifies the reason a licensor should have alternative options. Not only did the licensee walk away with an incredible deal for the consumer product line but also with the future rights to the enterprise and commercial audio systems.

The lesson learned here is that the licensor was desperate to get the deal done and failed to understand the basic guidelines for creating leverage during negotiations. The biggest mistake was not only failing to have a viable alternative but the licensor attempted to play his strength against the licensee.

An astute negotiator knows the greatest strength is to build a strategy that plays the potential licensees against each other. By concurrently negotiating with multiple candidate licensees, the licensor strengthens the negotiating position and the real market value eventually emerges.

The licensor’s goal is to create leverage to negotiate the best deal possible. Assuming the licensor has already established value argumentation for the IPR, there are several other techniques to augment leverage. The licensor has the option to hire a professional licensing agent or subject matter expert, develop a strategy, create a walk-away plan, perform due diligence, and identify alternative options while engaging in talks with the target licensee.

The licensor must ensure that there is not a fair fight at the negotiating table. The fairer the fight, the lesser the possibility for negotiating the best possible deal. A licensor who embodies hubris will usually come out on the bottom. The licensor who embraces humility improves the odds of receiving a palatable deal. Another way to say it would be “at the feast of ego, everyone leaves hungry.” VC

This article was originally published in Voice Coil, August 2014

Article by Eric Kowalski (Menlo Scientific)